This is the text of a talk I gave for the Women’s Grassroots Activism Conference.

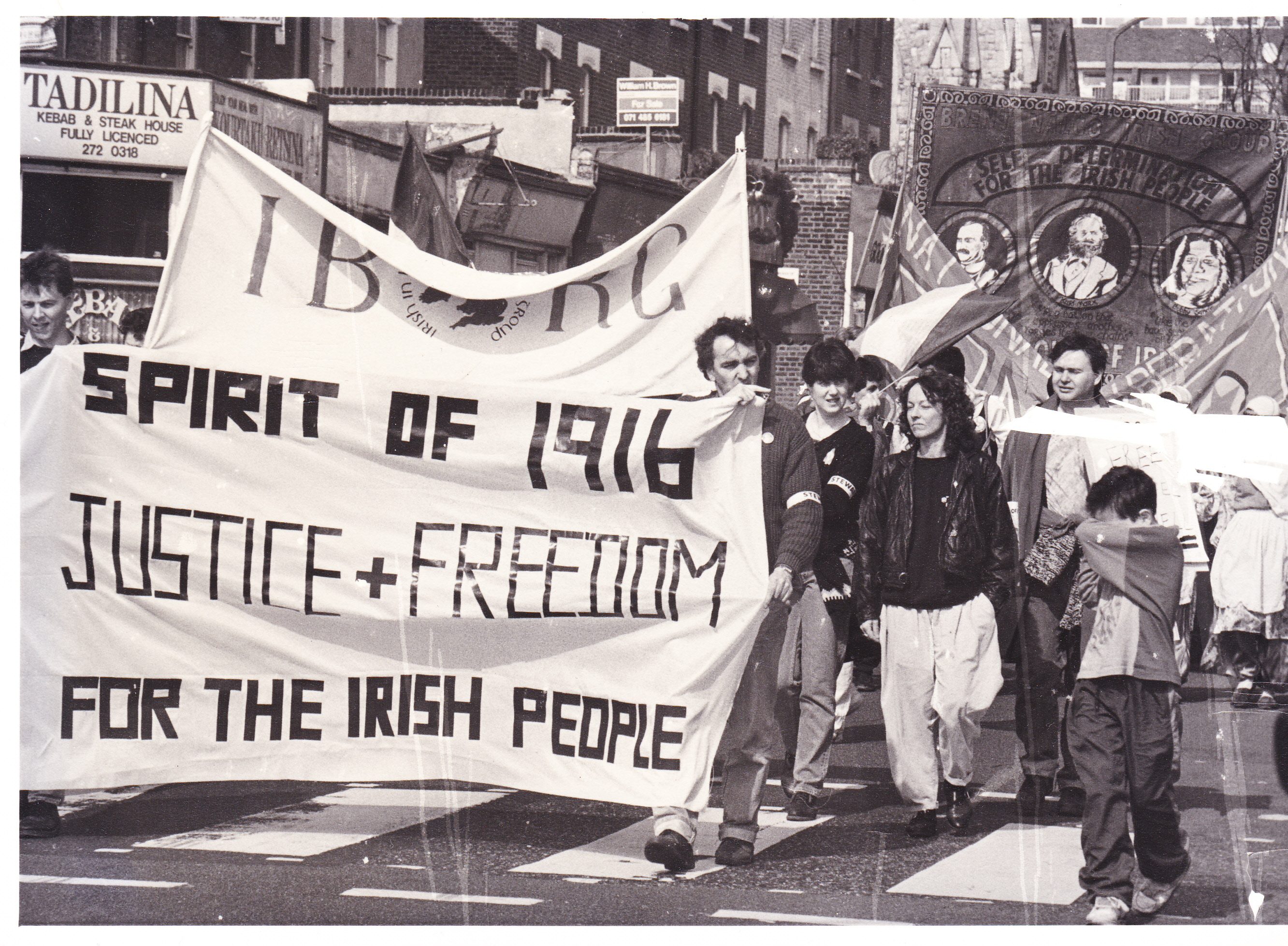

I am an activist, not an academic. I am Mancunian and second generation Irish. From 1985-2000 I was a member and a National Officer of the Irish in Britain Representation Group and I am now archiving the life of the organisation. The archive is at the Working Class Movement Library in Salford. https://www.wcml.org.uk/

In 1981 a new wave of Irish activists became involved in not just the campaign for a united Ireland but also civil rights and equality for the Irish in Britain.

These were critical times during the conflict in the North of Ireland; it was the time of the hunger strikes when 10 young men died for their right to political status.

It was a time when a new generation of second and third generation Irish people became active in a variety of organisations from the Troops Out Movement to the Irish Abortion Support Group and the Irish in Britain Representation Group (IBRG).

It was a time when there was an active group of people in the Labour Party who fought for a progressive policy on the North of Ireland and supported the rights of the Irish in this country while a number of labour Councils were prepared to fund groups such as IBRG.

At the same over 40,000 Irish women and men each year were travelling every to Britain for work, education, some of them joined organisations such as IBRG.

The IBRG was set up in 1981. It was a community-based organisation with branches across the country.

IBRG attracted not just a more politicised generation of Irish born and 2nd generation but also attracted women who played a significant part in the organisation as members and officers

From 1981 to 2001 there was a female president (Maire O’Shea), two female chairs (Bernadette Hyland and Virginia Moyles), two secretaries (Judy Peddle and Virginia Moyles.) There was a Women’s Subcommittee, a Women’s Officer (Majella Crehan) IBRG women’s meetings, while in common with many radical organisations at that time, crèches were provided for all national meetings.

IBRG took up issues affecting women in Britain and Ireland. This included strip searching, divorce, abortion, and contraception as well as welfare and civil rights issues

The IBRG had branches across the country, reflecting where the Irish were living. There were several in London as well as Birmingham, Cardiff, Coventry, Manchester, Bolton, N.E. Lancs, Leeds and Merseyside. Over the years branches flourished and declined by turn, reflecting the problems of organising events and activities and finding activists and funds to keep going. Central to its ethos was that it did not kowtow to the Irish government nor the Catholic Church, unlike the traditional Irish organisations.

Looking through the IBRG archive one of the defining characteristics of the organisation is the number of women involved – even its early days as Judy Peddle, National Secretary from 1983-85, who lived in Cardiff, recounts. “ in 1982 I became friendly with two London based members from Co Leitrim, Bridget Gavin and her late sister Colette They suggested I join and contacted the founder John Martin, who was working tirelessly across the UK to set up branches, and a small branch was set up in Cardiff.”

In later years National Secretary Virginia Moyles worked tirelessly to produce National Minutes which are a cornerstone of the history of IBRG.

Many women took part at a branch level; organising the meetings, fundraising, making links with other groups. In Bolton, the first branch I joined, the women involved included a teacher, a playwright, and several working- class woman , including Margaret Mullarkey who played a key role in the branch. In other branches Laura Sullivan in Hackney , Ann Hilferty and Joan Brennan in Manchester , Jodie Clark in Southwark, and Theresa Burke in Lewisham played significant roles.

Women from IBRG attended the annual International Women’s Day weekend in the North of Ireland to show solidarity with Irish women political prisoners.

In 1989 an IBRG delegation went to both parts of Ireland which included visits to women’s groups in Belfast, Cork, and Dublin.

In common with trade unions and other community organisations of this period IBRG gave women, and particularly w/c women, opportunities to educate themselves, including political education. It also encouraged women to believe that they could initiate activities and take positions of leadership within IBRG and other organisations.

In the 1980s a new wave of Irish women was organising not just in IBRG but in other groups including the London Irish Women Centre as well as issue-based groups such as abortion and strip searching. The biggest Irish community was in London: a number of Irish organisations funded by the Greater London Council and also some local authorities. IBRG benefited from this funding stream and we had several offices across London.

Jodie Clark’s involvement in IBRG reflected the way in which the organisation drew in Irish working- class women who were prepared to get stuck into grassroots organising, women who were experiencing anti-Irish racism of the everyday variety, but also the more corrosive institutional racism endemic in British society. Due to her experience of anti-Irish racism Jodie involved with the Tenants Association in Peckham. She says: “one of the first things I did was to make sure that anti-racism was in the constitution of the organisation.”

She went onto to join IBRG and with like-minded activists she was active in Southwark Irish Forum to represent the needs of local Irish people. Like other parents of children in IBRG her children were included in organising political events, going on marches and cultural events.

Manchester IBRG, unlike the London branches, had no funding or opportunities to set up funded groups. The Irish made up 10% of the Manchester population with a history of activity in Republican, trade union and labour movements from the C19th onwards.

Women played an important role in the branch. In 1990 19 of the 34 members were women. These women took the important roles; chair/treasurer and public relations officer were all women.

IBRG in Manchester attracted women because of its policies and because it was an organisation that, unlike other organisations, including trade unions, it was not dominated by men trying to make careers for themselves with women at the margins.

My experience in the Manchester Irish community was frequently one of rampant sexism by an older male hierarchy, often with business interests, who were also happy to exploit my father and his comrades on the building sites of the north west. It was not surprising that we attracted younger women and single parents who were not prepared to put up with the “parish pump” politics of the Irish Centre.

IBRG attracted women who had been active in the traditional Irish community but felt sidelined and also younger women who wanted to take up issues relevant to them.

IBRG offered them the opportunity to take positions in the branches and at a national level as well as taking part in campaigns that affected them and were important to them.

This included challenging anti-Irish racism, representing IBRG in meetings with the council and other organisations, supporting issues such as abortion and strip searching and campaigns including that of Kate Magee, and promoting Irish culture and history in the education service.

Laura Sullivan sums up her experience in IBRG

In IBRG the women also stood out for me. There were a few women that I worked with eg Virginia Moyles, Bernadette Hyland, Majella Crehan and Caitlin Wright. Among the things I did with these women was organise a workshop for Irish Women in Hackney with Virginia and was encouraged to write in the IBRG Magazine by Bernadette. I got asked to speak to speak at meetings, facilitate at conferences and attend delegations. Because I had a supportive group around me there was a belief, I could do things.